‘Trade not Aid’ is a provocative slogan for any development advocate. It overlooks areas, including humanitarian response, where no-one thinks trade can substitute. But more challenging is the suspicion of a cynical appropriation; replacing concern for global justice with a grasping, narrow self-interest.

This reaction is understandable, but we must resist it. To renew Labour’s approach to development, we need to recognise the essential progressive lessons that can arise from those three challenging words.

Let’s start with a basic truth: sustained reductions in poverty and inequality can only arise from economic transformation.

We are familiar with the consequence of the rapid economic growth in much of Asia over the past 35 years: 1 billion fewer people in poverty. Equally clear is the growth role of export-boosting industrial strategies that have moved, step by step, up the economic value chain, prioritising the sectors that made most sense for each country in its regional context.

90% of the variation in extreme poverty since 2000 can be explained by differences in national average income alone, showing that inclusive economic growth is simply essential for ending destitution. Alongside increases in income and employment opportunities, growth builds tax bases, enabling public services to be provided more sustainably and democratically.

The immediate attraction of boosting trade and investment with developing countries is therefore obvious: we can support poverty-busting growth and create UK business opportunities at the same time. Growth is central to this Labour government’s domestic agenda; it can sit at the heart of our development approach too.

In the UK, an economic turn in development practice is necessary to rebuild its reputation – with voters, including our ‘living bridge’ diaspora communities, and with our international partners.

This challenge must be taken seriously, given the future threat to development from the populist right. Recent surveys have found that only 43% of the public think the UK Government should give any aid at all, and only 21% see aid as effective.

Highlighting economic change has the potential to address public scepticism by showing intuitively how poverty can be reduced; the shifts we support for today’s lower income countries are essentially the same as our own path. By underlining this, we can erode the crude distinction between ‘rich’ and ‘poor’ countries that fuels negative stereotypes. More transactional voters can see development’s benefits to the UK more easily if our ways and means are interlinked with trade and investment.

And it is no less important to take the lesson from how diaspora communities and African leaders with a personal stake in development have defied expectations and welcomed recent shifts. This includes leaders with serious short-term challenges as a direct result of reduced aid spending.

Closer alignment with the agency and priorities of developing countries will be welcomed, and above all this means supporting economic transformation. A development policy toolkit centring trade and investment has the potential to be more impactful, and more politically and diplomatically sustainable too.

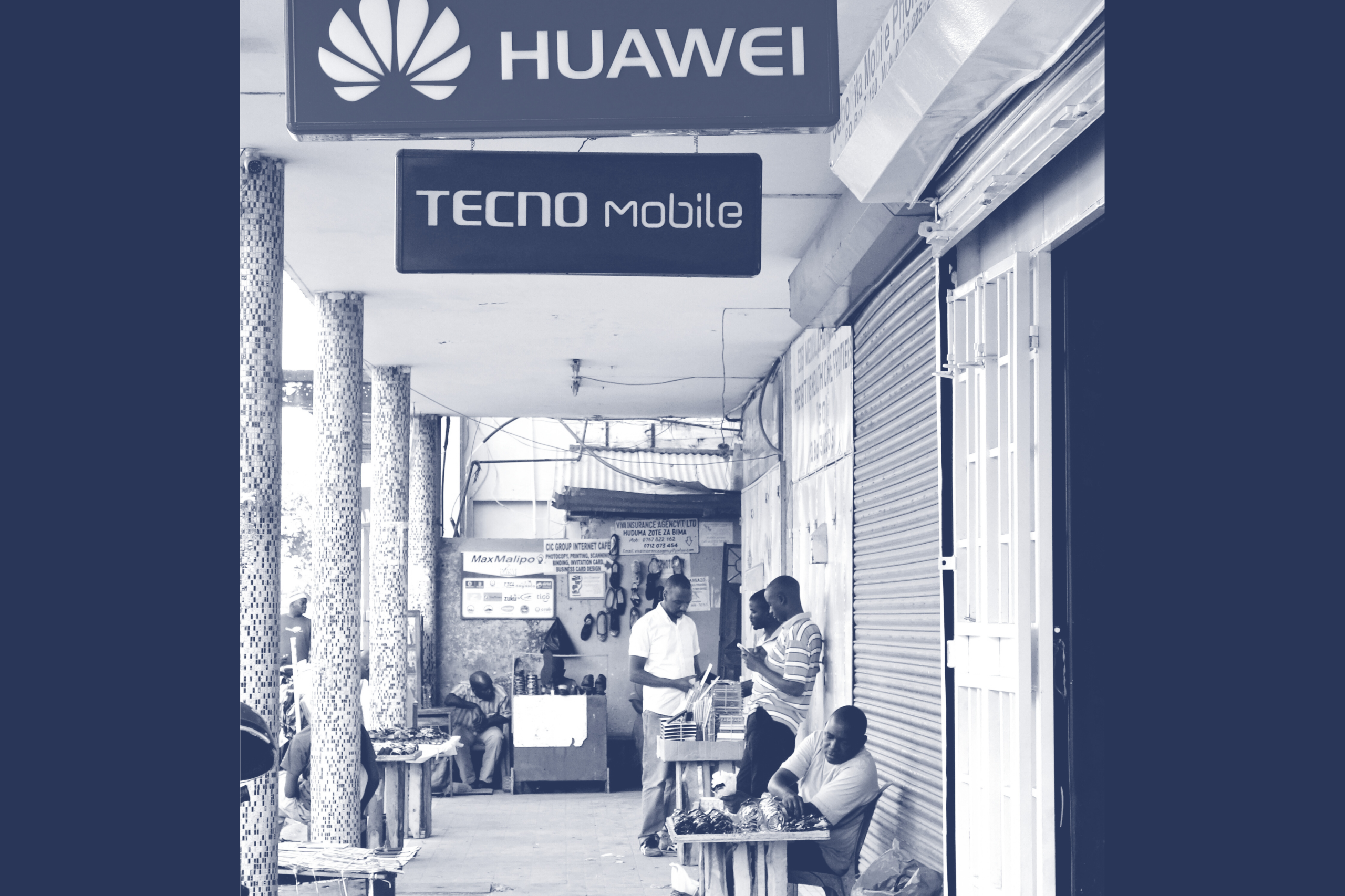

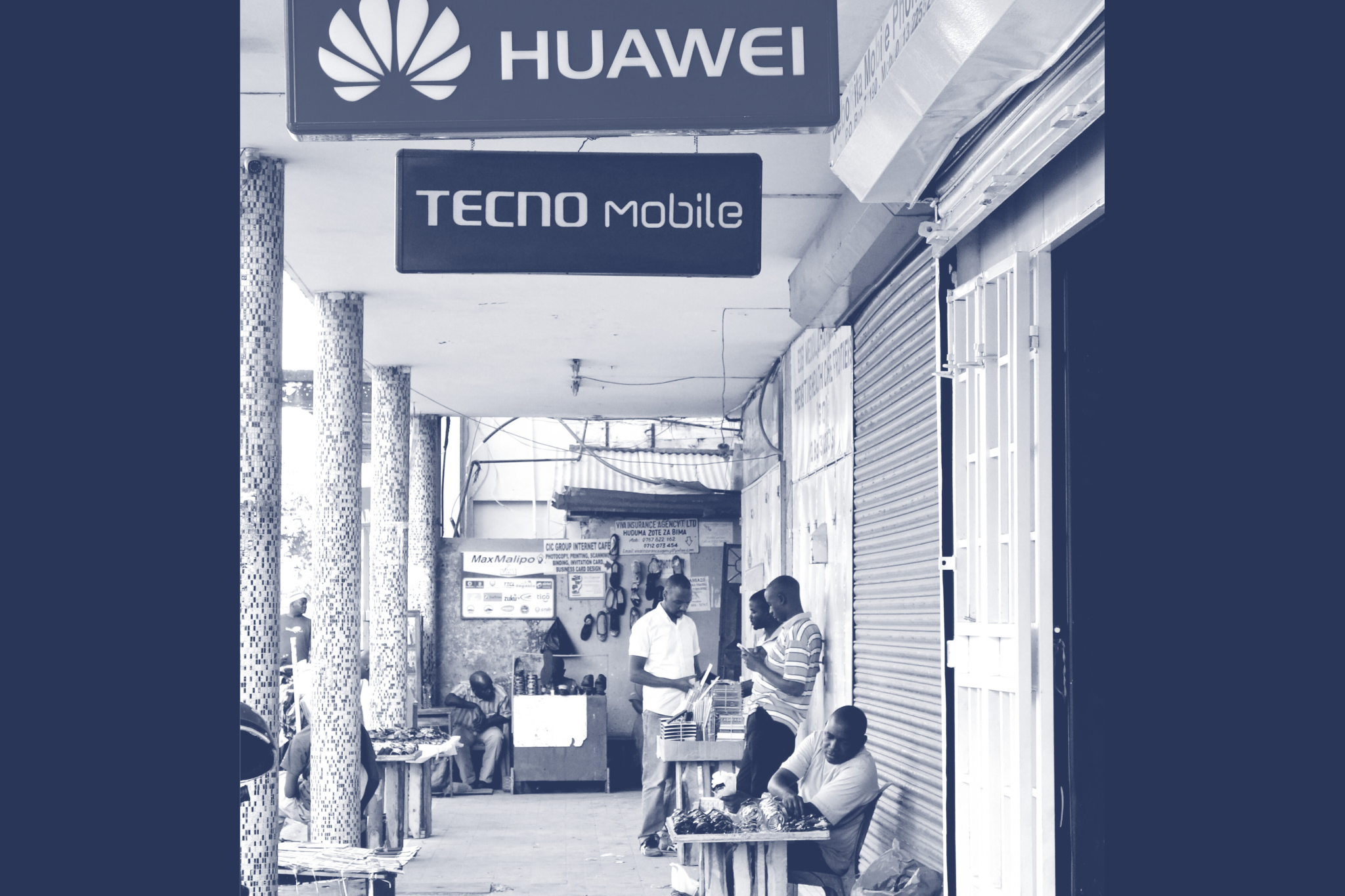

For decades, the UK prized a development reputation based on scrupulous separation between development aid, diplomatic advocacy, and private investment. China has never drawn a deep distinction between these domains. Far from creating mistrust, this seamless integration of self-interested and solidaristic goals is seen as more honest and reliable by developing country partners.

China’s synthesis has underlying advantages that we can and should seek to replicate, including the backing of consistent high-level engagement and long-term political and financial commitments. Above all, China meets developing countries on their own terms, not only showing respect to their economic ambitions but tailoring deliverable deals to match.

The credibility of these offers of cooperation is the core around which China has spun a successful diplomatic narrative, based on self-presentation as a champion of the ‘Global South’. After a decade when China has continued to hoover up developing countries’ raw materials as fuel for an economy now at the technological frontier of global capitalism, this narrative is wearing thin. Their manufacturers have flooded developing country markets, undermining their ability to follow the same industrialisation pathway that China itself did.

However, recognising the limits of this highly extractive approach to partnership, China is shifting towards a diversified ‘Hunan’ investment model. We can expect China’s economic engagement to become more willing to transfer skills and build value chains, rather than just sending in their firms, workers and capital in exchange for crude oil, iron ore, and burdensome debt repayments. This only increases the urgency for the UK and our allies to provide an alternative – distinguished not only by liberal democratic values, but by being even more in tune with the agency and ambition of our developing country partners.

To return to and sustain our role as development partner of choice, we cannot return to the old DfID model, despite its merits, but must build our own joined-up agenda. Learning selectively from China’s achievements, and the wider ‘South-South’ development paradigm, is essential to success.

There are many reasons to seek a greater prioritisation of trade and investment in UK development policy. But there are challenges too, not least the passive erosion of UK-Africa trade over the past 15 years.

Even in 2005, the UK was the single largest importer from Sub-Saharan Africa and was typically in the top three for bilateral trade throughout the 1990s and 2000s. But by 2021, the UK was no longer in the top three for any African country, contrasting not only with China, in the top three for 29 countries, but also India at 18, UAE at 16, France at 10, and Italy at 8.

This is interlinked with the greatest challenge: breaking the tendency to see trade with developing countries as the export of cheap goods, particularly primary commodities like mineral ores or unprocessed foodstuffs.

One reason that UK-Africa trade looks so meagre is because Africa is so frequently exporting low-value natural resources to third countries, above all China, before they are exported to the UK in finished forms. Africa receives little of the economic value from trading patterns like this – and what Africa loses in development potential, we lose in economic security as Chinese dominance over supply chains is weaponised.

As a largely services-based economy, there is limited scope for the UK to have a strategy based around increasing demand for basic commodities, if that were even desirable. Far more promising, both from an economic and development perspective, is trade and investment growth that matches UK strengths with African ambitions.

Within this, I would highlight four opportunity areas: electrification; growth in service sectors, including financial, creative, and digital; value addition in goods supply chains; and continental integration.

The electrification opportunity in Africa is huge, with 600 million people – 80% of the world total – still lacking reliable electricity6, but with the continent holding 40% of global solar potential. Africa’s solar imports have risen 60% in the year to June off the back of a temporary supply glut from China7, but there is enormous potential still unused. Even more work is needed to build resilient grids that can provide interconnections across vast distances while maintaining the reliable supplies needed for industrial growth. DRC could recover 30% of its electricity through grid improvements alone.

High-value services are a natural fit for many UK firms and institutions, but government can do more to support this. We should be facilitating these links by default in our economic diplomacy and recognising the mutual benefits that come from successful exports through our universities, specialist training colleges, and UK-based standard-setting institutions. To support service industry growth, time-limited mobility of people and ideas, and investment in people from developing countries are both key. This therefore requires us to push back against kneejerk politics which conflates accessible mobility for education, business, and cultural exchange with uncontrolled migration.

Value addition is the most challenging but also the most potentially rewarding area for UK investment. It promises to kickstart a self-sustaining and broad-based economic transformation in Africa, without which we will never eradicate the extreme poverty and structural inequality that mar our world. For example, to meet critical mineral security and development objectives alike, what we should want is Congolese cobalt being processed in Africa, not China8. But delivery against this agenda requires massive investment in infrastructure, skills, and policy and governance reforms. These investments are inherently long-term and unavoidably high risk/high reward – requiring an outsized role for government-to-government partnership in creating an enabling environment.

Continental and regional economic integration is equally vital for development, particularly in the form of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and its component Regional Economic Communities. The income and job growth from full implementation of AfCFTA would lift 50 million people out of extreme poverty by 2035 according to World Bank projections9. The UK was one of the first movers in supporting AfCFTA through our Memorandum of Understanding and early provision of expertise. If it is integrated with wider UK engagement and economic diplomacy, continued technical assistance through ‘Aid for Trade’ organisations like TradeMark Africa can build on our position as a major supporter of this agenda.

The UK has many tools in our toolkit, including the financial firepower of City investors and technical expertise that spans many sectors and every part of our country. For 2023, EY ranked UK foreign direct investment into Africa as most impactful, above the US and China, once job creation, capital investment and project count were taken into account.

Equally important is the depth of our trusted diplomatic network and our close strategic alignment with like-minded partners, including European allies, Canada, Japan and more. Our partners are grappling with the same geopolitical changes that we are, and adapting their foreign, trade and development policies in a similar direction. By bringing private and public sector capacities together through ‘cohering power’, we can ensure trade and investment have the largest possible development impact.

Exercising ‘cohering power’ means not just convening partners, but being proactive in assessing alternative infrastructure plans, sequencing projects across long time horizons, and building consensus. It means working more closely and consistently with developing country partners to match their strategies, plans and projects with the expertise and private sector resource needed to make them bankable.

Even infrastructure developments that are strategic priorities for major global powers, including the United States of America and the European Union, can lack the coherence needed to ensure their development potential is delivered. A prime example is the Lobito Corridor connecting Angolan ports with the critical mineral rich Copperbelt. Lobito, like other rail corridors in the Southern Africa region, holds the potential to radically increase the reliability and speed of freight connections, catalyse industrial growth, and enable population movement, opening up agricultural and other economic opportunities in a region affected by some of the worst extreme poverty and food insecurity in the world. However, none of this is an inevitable result of infrastructure investments if they are designed to benefit narrow interests, or if they only make progress by being broken up into less coherent and impactful sections.

UK firms and finance cannot deliver transformative infrastructure like this alone – but no-one is asking us to. What I do hear consistently from partners is a desire for UK leadership to bring the pieces together, apply a regional lens, and work consistently to ensure impact and delivery.

The components of a progressive trade and development agenda are already coming together. The government’s forthcoming Africa Approach has reset our bilateral relationships and refocused attention onto Africa’s priority of trade and investment.

Earlier this year, rules of origin under the Developing Countries Trading Scheme (DCTS) were revised to enable value cumulation across 50 African and 18 Asian countries. So long as the final stages before export to the UK take place in a DCTS country, the whole process will receive preferential trade treatment; a vital support to intra-Africa trade and regional industrial policies.

UK Export Finance (UKEF) is engaged in a strategic review, applying economic security and development lenses to trade finance to identify better ways to create balanced trade partnerships.

However, the 2025 Spending Review has simultaneously delivered real blows to the coherence of UK Africa policy. Cuts to Department for Business and Trade expertise across Africa have been brutal, with 60% of posts lost, a notably higher percentage than other global regions. The rationale is clear, but only if we prioritise from a narrow, near-term perspective. Growth for the UK is clearly harder to achieve in Africa than in wealthier areas where trade volumes start out much higher. However, such a short-term lens necessarily misses out vital cross-government objectives, including those stemming from geopolitics, economic security, and, above all, development.

Responding to this resource challenge requires us to break down policy silos and ruthlessly prioritise. I recommend:

Far from ‘using’ development for narrow business, diplomatic or national security ends, this agenda is about understanding UK and developing country interests holistically, looking at the tools available, and then integrating policies across Departmental silos.

We need modern development voices in the room for the government’s big international decisions, including those on critical minerals and trade finance. Without that broader perspective, we will fail to achieve the national security and growth that are so vital for our country and our world to have a progressive future.

‘Trade not aid’ need not be a call to abandon development expertise. Far from it, our development specialists must be empowered to play a more strategic role. But we must recognise that the future of development lies in shaping our economic diplomacy and aligning with developing countries’ own ambitions – putting economic transformation first.

Next year Progressive Britain will be releasing a collection of essays like this one covering perspectives on development from our leading MPs. Make sure you are subscribed to the newsletter for updates.