As the final draft of the MoD’s Defence Investment Plan works its way round Whitehall it seems unlikely that it will have any firm commitments on increasing service personnel numbers. This will disappoint Healey and other Defence Ministers but they are realistic. They know they operate in a policy environment which still prioritises spending on capital investment, not on people.

One of the challenges they have is to explain to their Ministerial colleagues that yes drones have transformed the battlefield in Ukraine but without the right numbers of skilled and resilient Ukrainian soldiers to operate drones Putin would be parading through Kyiv today. In a recent speech Healey reinforced that message

“it is our people who win wars, people who demonstrate deterrence, it is people who keep the peace…………In the years ahead, we will be asking more of those service personnel,”

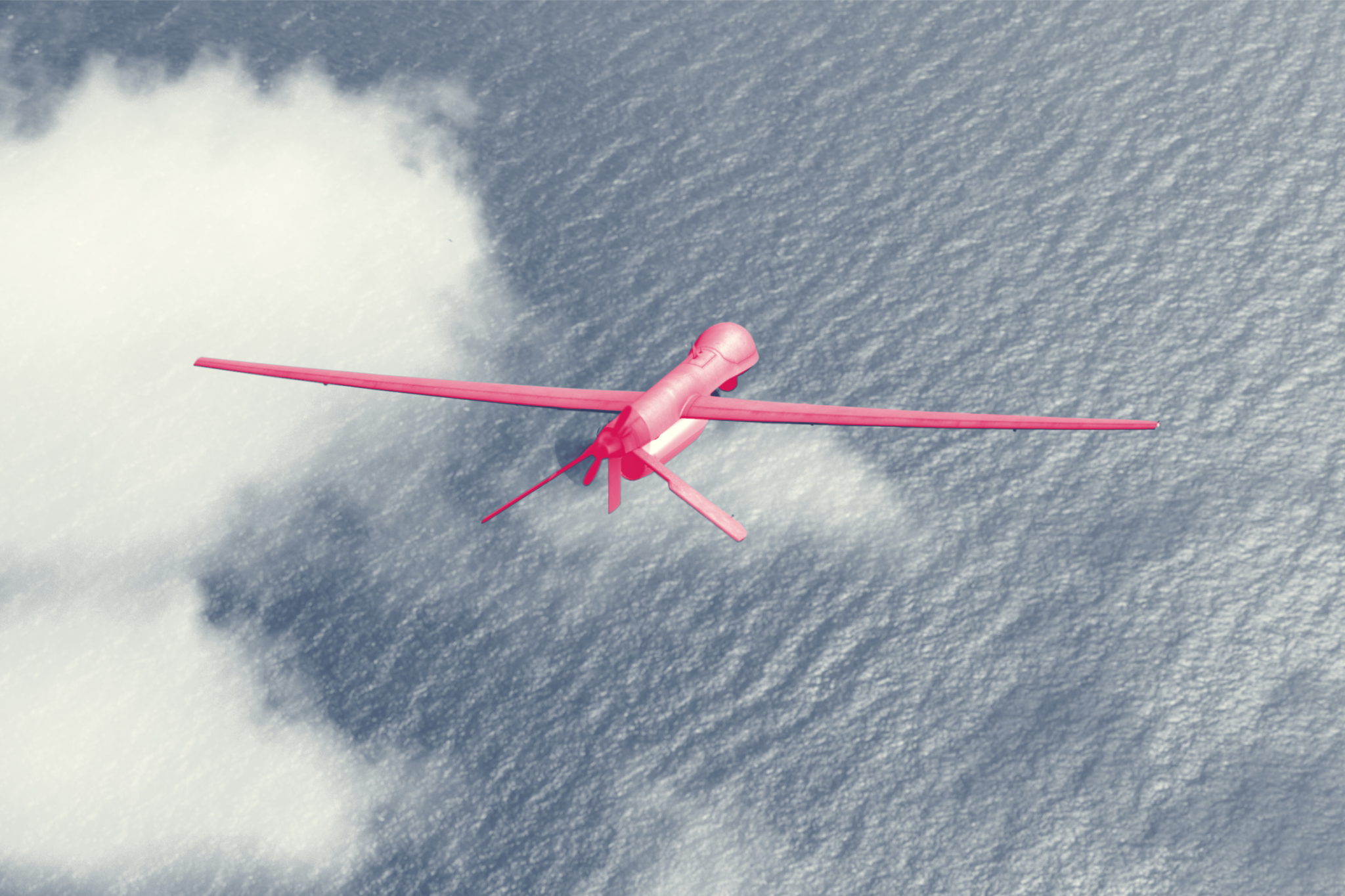

As he pointed out 80% of casualties in the Ukraine war are accounted for by drones. While the use of AI and automation is developing almost all of the drones used in Ukraine require some form of human involvement. In addition, many of those casualties come from drones linking to conventional artillery, which even with automated loading systems still requires people.

Drones are often referred to as “uncrewed” but that description is too often misinterpreted. Most drones cannot fly without some form of human control. Yes, AI is often essential in ensuring they are effective in gathering data and striking targets. However, the evidence is clear. Without people drones would not have delivered anything like the effects that we see today in Ukraine and so many other conflicts across the world.

In a speech earlier this year, the Head of the British Army, Lt Gen Walker said that he wants to spend

“50% of our money on the 20% of crewed and expensive, and 50% on the remaining 80% of attritable”

One of the key questions that his staff have had to answer is how much of the 50% of funding that is going to be spent on “attritable” capabilities needs to be spent on equipment, and how much on training and paying the soldiers who will supply, maintain and operate this equipment? Increasingly military equipment will be uncrewed, but it will continue to need large numbers of people to make it effective, even if they are not physically close to the systems they are using. After all, if the Ukrainian armed forces could replace most of their soldiers with fully autonomous systems which do not require any human input they would probably have done so by now.

The claims made by some in the private sector that fully autonomous systems will become the dominant weapon on the battlefield seem motivated by not just increasing profits but in some cases by hubris. Similar claims were made about how new military technology, such as the machine gun or the strategic bomber, would reduce or eliminate the need for mass armies. The sacrifices we recall on Remembrance Sunday are testimony to the invalidity of these claims.

At Staff College senior military officers are taught about the numerous examples of how new weapons that promise to deliver victory are countered by the adversary developing new tactics, strategies and/or technologies that successfully negate them. In the case of AI this might include the use of data poisoning attacks or other tactics that can be used to create ineffective or even dangerous algorithms. That does not mean that military technology remains static. The tank has replaced the horse, and perhaps the drone has already or will replace the tank. However, the need to invest in people remains the essential element in delivering long term national security for the UK. As the MoD’s own think tank has pointed out

“Irrespective of any equipment choices……… the training, ethos and morale of a state’s armed forces will remain critical factors in attaining defence and security advantage out to 2055.”

Currently most of the increase in MoD spending will go on equipment but Healey and his colleagues will continue to make the case for transferring at least some of that capital spending to the training, recruitment and retention of service personnel. This is a debate that will be followed in Westminster, Whitehall, Paris, Washington, Berlin and critically Moscow and Beijing. Getting the balance right between capital and resource spending is not an obscure accountancy – it as a key test of the seriousness with which Labour Ministers approach defending the UK.

Josh Arnold-Forster is a political consultant specialising on UK defence issues. He has worked for two Shadow Defence Secretaries and was a SPAD for Defence Secretary John Reid MP.

View all posts